St. Patrick’s Church

Building a New Church

As with many Manx parish churches, Kirk Jurby was deemed to be in a ruinous state by the end of the 18th century and too small to meet the needs of the parish. In 1813, as was the law at that time, Tynwald was petitioned for permission to build a new church and work began on taking down the old church. An assessment was made to determine how much each parishioner should pay towards the cost of building the church. The parishioners were invited to “take their pews” in 1818, and in 1819 the churchwardens handed over the accounts to Bishop George Murray. It was to be another 10 years however before all the bills were paid and the church could be consecrated.

Each quarterland was entitled to a pew. The front Southside pews were allocated to East Nappin, next to the church and owned by the Captain of the Parish Robert Farrant, West Nappin, where St. Patrick’s Chapel was sited and Ballacurrey, site of an early keeill where Early Christian crosses were found.

Several of the farmers had land in more than one quarterland and there were also the intack lands. These were lands licensed to be enclosed. Although some of the bigger landowners or tenant farmers may also have had land in the intacks, they were usually farmed by the crofters of the parish.

The Farrant Family

The Farrant family lived in the parish of Jurby for around 100 years, from the end of the 18th century to the end of the 19th Century, but their influence in the parish endured long into the 20th century and their lasting legacy is Jurby Church as it is today. In 1787 Robert Farrant married Margaret, daughter of Richard and Ann Moore. Ann was from the Christian family at Milntown and was to become heiress to the Ballamoar and Nappin estates. Robert, Margaret and their family lived with Ann at Ballamoar mansion house.

In his role as churchwarden Robert played an important part in getting a new church for the parish. At the time when the church was being built, Robert and then his son William, refused to pay the tithe on potatoes, the staple food of the poor, to Bishop Murray. After an appeal was won by the Bishop the first public protest meeting was held in Jurby with William Farrant addressing the meeting. Protests and riots soon spread to the other parishes and the tithe was abandoned.

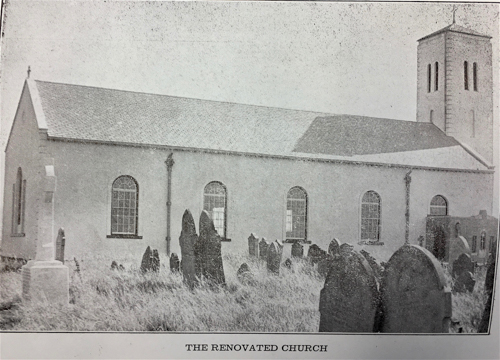

1939-40 Renovations

By the 1930s Jurby barely existed as a parish. The school had closed, the church was in a bad state of repair, the roof was in danger of collapsing and it was in danger of closing. A large sum of money was needed to renovate the roof, tower and outer walls of the church.

The Jurby Chalice

The Reformation saw the gradual elimination of Papists from the ranks of the Clergy. It is recorded, however, that one Manx vicar at least held his vicariate till his death, which was described as that of “the Papist.” All Communion plate was melted down or disappeared from the Island with the exception of the silver paten at Kirk Malew and the silver chalice in St. Patrick of Jurby.

In 1939 Deemster Farrant proposed that the chalice should be sold to repair the church and it was feared that it would have to be sold outside the Island. As a trustee of the Manx Museum, Deemster Farrant negotiated the sale of the chalice to the Museum for £1,000 having organised an appeal to raise funds to pay for it.

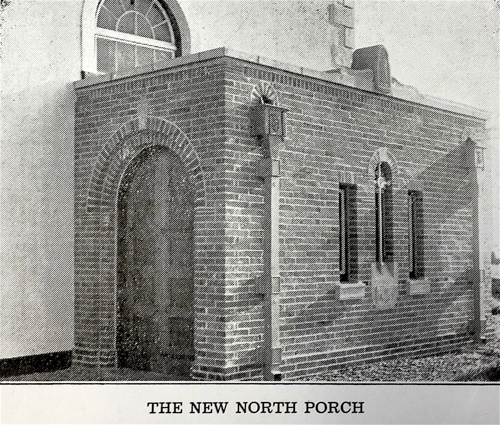

The proceeds not only paid for the re-roofing and repairs to the church, but also the lowering of the tower with a pyramidal top, and the addition of the porches on the north and west walls of the building.

The North porch houses the Jurby Manx Cross-Slabs. There are also pictorial references to St Patrick in the floor tiling and the relief figure in York stone on the coping.

The beautiful cruciform stained glass panels in the doors of the west porch reflect the history and life of Jurby and the Island.

St. Patrick’s Chapel was made into a school dedicated to St. Cecilia in the 18th century and this panel was beautifully restored by Robert Bullock in 2019.

Three window panels in the North porch were commissioned by the RAF in 2002. The panels have etchings of Second World War aircraft, in memory of the aircrew who died during the War.

At the back of the church there are memorials to those remembered on the War Memorial and the War Graves. Burial records, books and other materials can be accessed by visitors to the church researching family history.